Rotating things in your mind is not imagery

Over the past 42 years, so-called mental rotation tasks have been used as one of the primary measurements of mental imagery in research. However, over the last few years, the use of these so-called mental rotation tasks has been questioned.

The classic version of these mental rotation tasks involves different shapes made of cubes and a participant has to compare two different cube shapes and say whether they are the same or different In the original paper from the 1970s, the authors showed that as the two objects were more different in rotational angle, as in one had been rotated more, it took people longer and longer to do the task correctly.

Over many years of research during what has been called the 'mental imagery debate' many authors argued that this time to complete the task as a function of rotation angle of this shapes was evidence that people were using mental imagery to do this task. The greater the angle objects had to be rotated, the longer it took because people had to reverse rotate those objects in their mind's eye. If you have aphantasia and find this concept strange, maybe you've seen architectural or computer aided design programmes on a computer rotating an object around, so what I'm talking about is a little bit like that, but in the mind's eye.

A few studies have attempted to assess mental rotation in aphantasia. An early single individual case-study of an acquired aphantasia patient MX suggested that MX took more time to respond and showed a non-linear function of response time to rotation angle, compared to controls on a 3D-block rotation task. However, despite differences in reaction times, MX could still perform the task accurately, providing evidence that their visuo-spatial ability remained intact despite the loss of visual imagery. This finding was recently replicated in patient MX several years after the original study, using the same mental rotation task.

In conflict to this, two recent studies report similar accuracy and response times in two types of mental rotation tasks between those with and without imagery (Milton et al., 2021; Pounder et al., 2022). Suggesting potential performance without imagery, however, how aphantasic participants achieve such performance, and if a sensory representation forms, remains unknown.

Recently, we aimed to assess whether being able to create and manipulate a visual representation in the mind’s eye is necessary to successfully perform a range of mental rotation tasks. We did this by recruiting large samples of individuals with aphantasia, (you may have been a participant in one of these studies- thank you so much!) We then compared performance with those with imagery in a typical range, on three different types of mental rotation tasks.

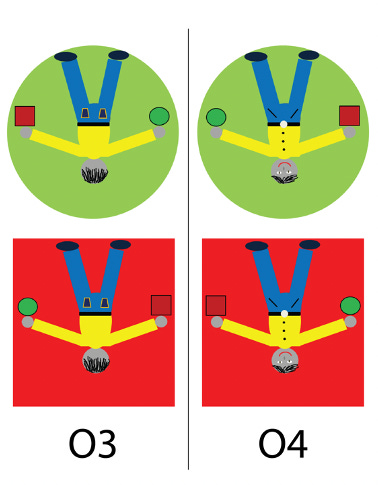

The classic Shepard & Metzler (1971) 3D block task see below, a version of the human mannequin (yes human shaped mannequin; see the red and green images below) test of spatial orientation and transformation, and a novel abstract stripy-pattern rotation task in which participants are asked to rotate an oriented pattern and the final position is objectively probed using the visual illusion of binocular rivalry - similar to our classic binocular rivalry method to measure imagery.

We further, investigated the strategies used by participants to perform these tasks to shed light on how one might perform so-called mental rotation without rotating a mental object at all.

Heres what the cube shapes and mannequins look like:

And here is the reaction time data

As you can see both groups clearly show this classic positive slope as a function of the angle of rotation. This means that people with and without imagery took longer the more the two blocks were rotated away from each other. The classic signature of the mental rotation tasks that people had interpreted to mean that people were using mental imagery for the task. As you can see in the data the aphantasia group responded a little bit more slowly on average compared to controls.

And, here is some data showing percent correct for the people:

What's interesting here is you can see that those with aphantasia are responding more accurately than those with imagery. When you combine the slower response times with more accuracy, we call this a speed accuracy tradeoff. In other words, those who don't think in pictures were taking a little bit longer, but being more accurate. This is a typical pattern we often see in decision making research, you can go faster, but end up being less accurate, or you can be more accurate, but a little bit slower.

Likewise, we see something similar with the mannequin test:

Finally, here is some data from the new pattern rotation task.

This new pattern rotation task is different to all the other mental rotation tasks, because rather than just comparing two different objects (same or different) we used our binocular rivalry method to probe any representation that might be there at the end point after the rotation.

So let me unpack this a little bit: when doing this experiment you had to look at a vertical or horizontal stripy pattern, then while that pattern was on the screen you had to rotate it about 45 degrees, then only after that the binocular rivalry illusion would flash on. So we were using binocular rivalry here to assess if individuals were able to rotate that pattern in their minds eye. As you can see in the data those with imagery in the typical range, in the pink colour, aka controls, were able to do that and got priming above chance. Whereas despite a couple in the aphantasia group getting an effect here, the majority of those with aphantasia did not get any priming, e.g. the data points are around 50% on the graph.

These data I'm showing you, again like last week have not been published yet, they have not gone through the typical peer review process that we do in science, so keep in mind that any data you see in a final published paper could differ or have a different interpretation, its unlikely but can happen. I always like to point this out when I'm showing people data that is unpublished.

That being said I think these data are really interesting for a number of reasons, one it clearly shows that you don't need to have mental imagery to do these classic mental rotation tasks, the 3D block and the mannequin tasks. There has been hundreds of papers in the last 42 years using these methods as a way to assess mental imagery, particularly work in the clinical psychological domain for example. Now we haven't used this task much here to measure imagery, we prefer the objective reliable techniques like binocular rivalry or pupil response or if online a questionnaires. However, now we know that you don't need imagery to do these tasks, it does bring into question the results of so many papers over the last 40 years and the results of those papers have influenced other papers and so on, and I think it's really interesting to start unpacking that and figure out how many conclusions we have about mental imagery may in fact, not be valid based on these new results.

For those with aphantasia, I think it is nice to find more evidence that while you may not have imagery of objects, spatial information for tasks like this one is clearly there.

Hyperphantasia

We are currently on the lookout and doing a bit of a drive to find more people with hyperphantasia, as we really don't know much about it yet and urgently need to know more. Not just to understand it, but also to shed light on imagery in general, including aphantasia.

If you know of anyone with hyperphantasia, please forward this message to them, if they want to be part of our reseach database to take part in valuable research they can sign up here.

My new book and imagery stories

I'm writing a book at the moment about mental imagery, I would love to include stories and personal experiences from those with aphantasia and hyperphantasia. If you have any stories about how your imagery or lack of it, has affected you, something you were doing, a decision, athletics training, meditation or anything else please send over a short description - that would be amazing!

Here is our lab site on Aphantasia where you watch and read more about our work. And, as always, please give me feedback on Twitter. Which of the above is your favourite? What do you want more or less of? Other suggestions? Please let me know. Just send a tweet to @ProfJoelPearson I always announce our new research on twitter with plenty of discussions! Have a wonderful weekend, all. Much love to you and yours, Joel