Flight Of Fancy: Why Do We Daydream And When Does It Become A Problem?

Escapism is important — but in excess, daydreaming can become a nightmare for our productivity, relationships and goal fulfilment

Future Minds newsletter breaks down the science of the mind and brain into short and easy-to-digest insights and actionable take-homes. Sign up and join the many others who receive it directly in their inbox.

Hello dear readers,

Imagine this.

You’re cruising down the highway in your open-top Porsche. The Hollywood sign sits resplendent in the background, as you feel the sun on your face and the wind blowing in your hair.

A call comes through on the hands-free speaker. It’s your agent, telling you that you nailed that audition last week and they want to offer you that role in a major Netflix show. But, there’s only one caveat — you have to spend a month in the Maldives filming (oh no, what a shame!)

Grinning as you hang up the call, you see a group of people on the side of the road. As you zip past them, they instantly recognise you. In unison, they begin chanting your name.

But suddenly, their chants become less friendly and more hostile. Annoyed, even. Then, you snap out of your reverie and realise that the group of ‘adoring fans’ is actually your exasperated partner calling your name to get your attention. Sigh, back to reality.

If you’ve ever had an experience like this one, then congratulations — you’re a human being. To a certain extent, we all daydream. It’s a healthy and important way to imagine future possibilities, explore new connections, and process thoughts and emotions.

But, if you find you can’t focus on any task for long before your mind begins to drift. Or, if you spend hours every day locked in a daydream… then, it could be a sign that your imaginary life has started to overtake your real one.

The science of daydreaming

First, it’s important to understand how and why we daydream. Because it’s different from just having a dream (the kind you have when you’re asleep) with your eyes open.

Daydreaming is the (mostly) spontaneous cognitive process that occurs when our brains are not actively focused on any particular task. Rather than ruminating on the past, daydreams tend to either be future-focused or exist in a kind of alternate reality (ie. imagining what it might be like to have someone else’s life).

When we’re cognitively idle — think, when you’re doing a task on autopilot like driving, or just before you’re about to drift off to sleep) — the brain activates a collection of regions known as the Default Mode Network (DMN).

Connecting the medial prefrontal cortex, medial and lateral parietal cortex, and temporal lobe, activity in this network has been linked to self-referential processing (thinking about oneself), episodic memory (recalling past experiences), and imagination (constructing future scenarios). These work together to create the experience we know as daydreaming.

Some argue that daydreaming may have an evolutionary function, as early humans are thought to have relied on it for scenario building, problem-solving, and preparing for potential dangers. And while our lives have changed dramatically since then, daydreaming still has utility today, too.

Firstly, daydreaming plays an important role in creativity, particularly in terms of divergent thinking (generating an array of novel solutions to a problem). In fact, some of the world’s greatest advancements and art were conceived in a daydream — from Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, which emerged from a ‘gedankenexperiment’ (thought experiment) where he would envision himself riding a beam of light, to JK Rowling, who invented the world of Harry Potter on a delayed train from London to Manchester.

The ‘mental time travel’ that happens in daydreaming is also important for solidifying our sense of self, by creating a thread between the past, present, and future. As well as boosting our self-esteem and optimism, it can help us set goals that are aligned with our personal values. When focused on positive experiences, daydreaming is also a valuable tool for managing stress and anxiety (and, interestingly, low default mode network activity has been linked to mental illness and loneliness).

But, as with all good things, when we begin to over-rely on daydreaming as a crutch, that’s when problems arise.

Mind wandering and maladaptive daydreaming

There are two main ways in which daydreaming can turn into a nightmare, for our productivity, relationships, and goal fulfillment.

The first is what we might call excessive, unintentional mind wandering. Research estimates that most of us spend 30 to 50 per cent of our time engaged in thought processes unrelated to our current actions or environment. Think, planning what you’re going to do on the weekend when you’re working on an important project or playing with your kid. While common, this can be problematic as it means we’re disengaged from the present moment. Not only can this be dangerous in certain situations (such as when we’re driving), but it also means we miss out on the benefits of things like getting into a flow state.

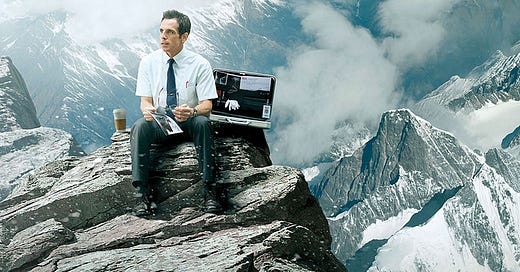

Less common but more troubling is maladaptive daydreaming. This is when someone spends excessive time (sometimes, up to six or eight hours per day), immersed in vivid and intense daydreams. Dialling up the escapist nature of daydreaming, this behaviour often emerges as a way to disconnect from real-life issues or anxiety. Many maladaptive daydreamers report seeing hyper-realistic, film-like narratives in their minds. While this may sound impressive, it can be extremely distressing — as it can feel like they’re locked in their brains. You only need to watch the film The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty to get a sense of how disruptive this can be to someone’s real life and personal relationships.

As maladaptive daydreaming is not officially recognised as a psychological disorder in itself, there’s no official treatment. However, as it’s linked strongly to ADHD as well as OCD, PTSD, and some dissociative disorders, treating the core symptoms of these conditions may help.

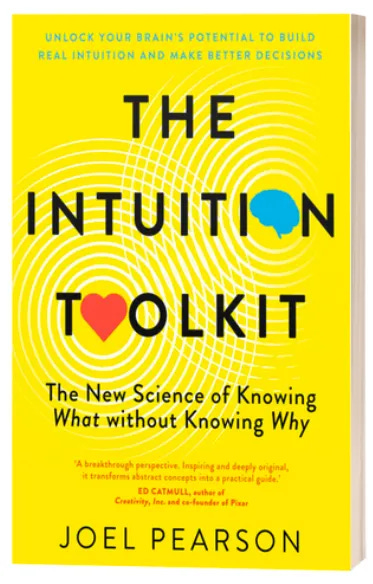

There’s also some evidence that both excessive mind wandering and maladaptive daydreaming are linked to hyperphantasia (where individuals have excessively vivid mental imagery). Our lab has conducted a study exploring the relationship between mental imagery and daydreaming, and we look forward to publishing the results soon.

How to be a conscious daydreamer

Perhaps the biggest thing that distinguishes daydreams from regular dreams is the fact that we do have some conscious control over them. When we’re asleep, our subconscious minds conjure up abstract and sometimes nonsensical scenarios, and we’re simply along for the ride (unless you’ve mastered the art of lucid dreaming).

Meanwhile, daydreaming is, by nature, self-directed. While our brains can take us down some unexpected paths, ultimately you’re the one in the driving seat. And, you can use that to your advantage by intentionally using it to solve problems, dream up new ideas, or even manifest your desires.

The key word here is intentionality. Rather than waiting for your mind to wander at inopportune moments, it can be helpful to make space for reverie in your life. Consider incorporating more activities into your day that will activate the default mode network, such as going for a walk (with or without music), free-form drawing or journaling, or even meditation.

It can also be helpful to set a theme for your daydreaming sessions. Perhaps you want to envision your goals for 2025, or think through a solution to an issue you’re having with a friend.

The point isn’t to be too restrictive, as you don’t want to block yourself from discovering surprising new insights. But, having some direction can be helpful, to prevent you from venturing into less productive territory (like, that Porsche you want to buy but can’t afford).

Mental meanderings

Do you think daydreaming is more adaptive or maladaptive?

Has your daydreaming ever got you into trouble?

What’s the best idea that’s ever come to you in a daydream?

Hey Joel, did you mean to say those of us who can't daydream aren't human? That would explain a few things lol.

Fantastic explanation of how daydreaming works that got me thinking about the implications that lack of daydreaming would have on the psychological development of kids.

When I first told a close friend I had Aphantasia the first thing she said was "lucky you, no daydreams to distract you"

The inability to visualize future or alternate scenarios definitely feels like something that has had an impact on my way of being and how I think about the future. It feels like one of the reasons I learned to be an excellent problem solver and quickly adapt to new environments. Everything is a new "problem" all the time when you live in the moment, don't remember much and can't imagine what's coming.

How's that for meandering?

Thanks so much for this article Joel. I have multisensory aphantasia and SDAM, and I don't have the types of daydreaming experiences you describe. I do sometimes get lost in a train of deep thought, but my experience is always very much grounded in the here and now. Is there any research on the default mode network in people with aphantasia?

Also, I'm genuinely fascinating to read about how much time people can spend daydreaming. While it might be nice to escape to another imaginary world, I often wonder how visualisers concentrate or get anything done!